Gender-based Violence on Rural Chinese Women Investigated through Land Ownership

“The gender-based structural violence against rural Chinese women shows an affordance to constructively reshape the dynamics between them and their hostile context. This essay proposes a trans-regional women’s collective that enhances their women’s physical and political situation in the current context, specifically by replacing the binary condition that makes their identity ambiguous with a third entity that they can always re-identify with.”

Medium Design, Fall 2020

Instructor: Keller Easterling

Featured in Retrospecta 44

Instructor: Keller Easterling

Featured in Retrospecta 44

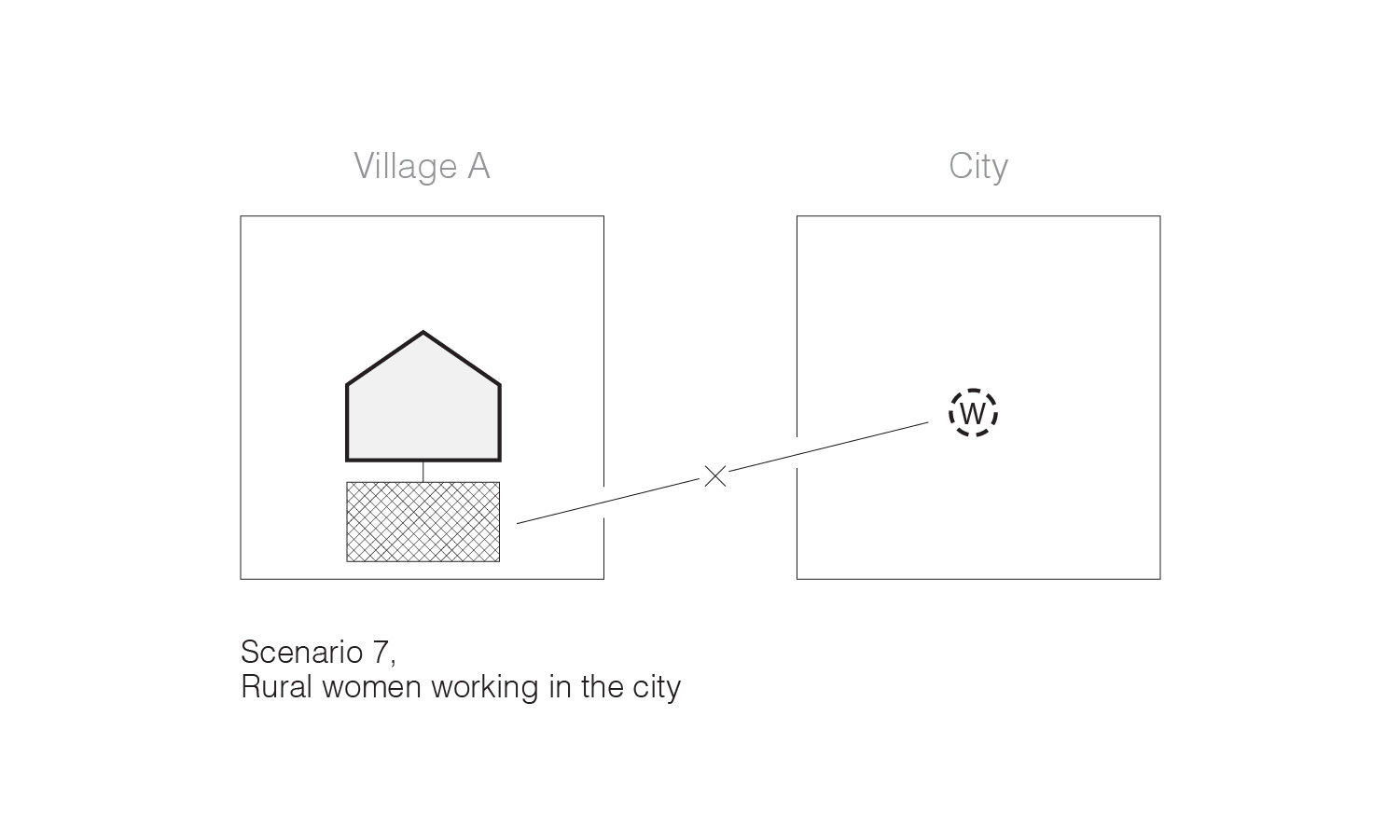

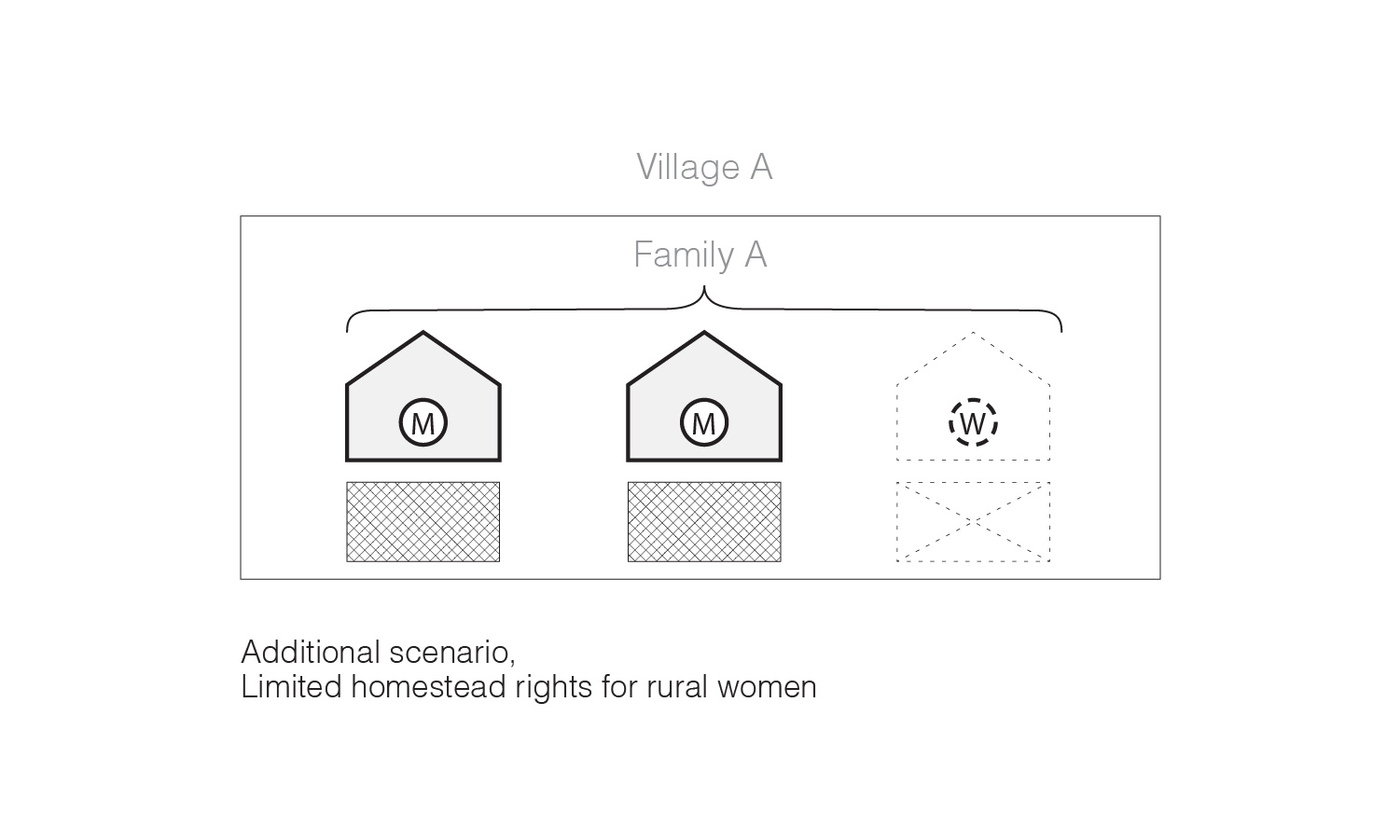

Land, especially in the rural Chinese context, grants more than just a piece of ground and the products that it provides. It affordsinformation, relationship, hierarchy, temperament, and everything else that determines the status of the owner in a rural collective. From the division of each family lot to their proximity to water source, land and its associated qualities shape the geopolitics of Chinese villages. The land is never static, but the binary nature of land borders resists these alterations. Boundaries, people, and legal regulations—the dialogue among these three actors therefore determines the landscape as well as the associated power interplay in a village community.

As the negotiation of these factors demands compromises, rural Chinese women’s land rights and interests are taken as casualties. Their identities are regarded as manipulable and thus rejected as needed, as the temperament of the legal structure determines that rural women’s disadvantages are invisible to the community that they function within. This essay argues that the ambiguity of rural women’s positions within their communities calls for a reversal of the existing power dynamics; the current disadvantages of rural females can be utilized as an affordance to generate a flexible, agency-giving condition that counters the reluctance from their dependents. It also suggests that to navigate within the current context, an effective, sustainable readjustment of land assignment needs to happen from within—this essay proposes a trans-regional women’s collective that can take on both political representation for women and physical re-adaptation of the land in rural China.

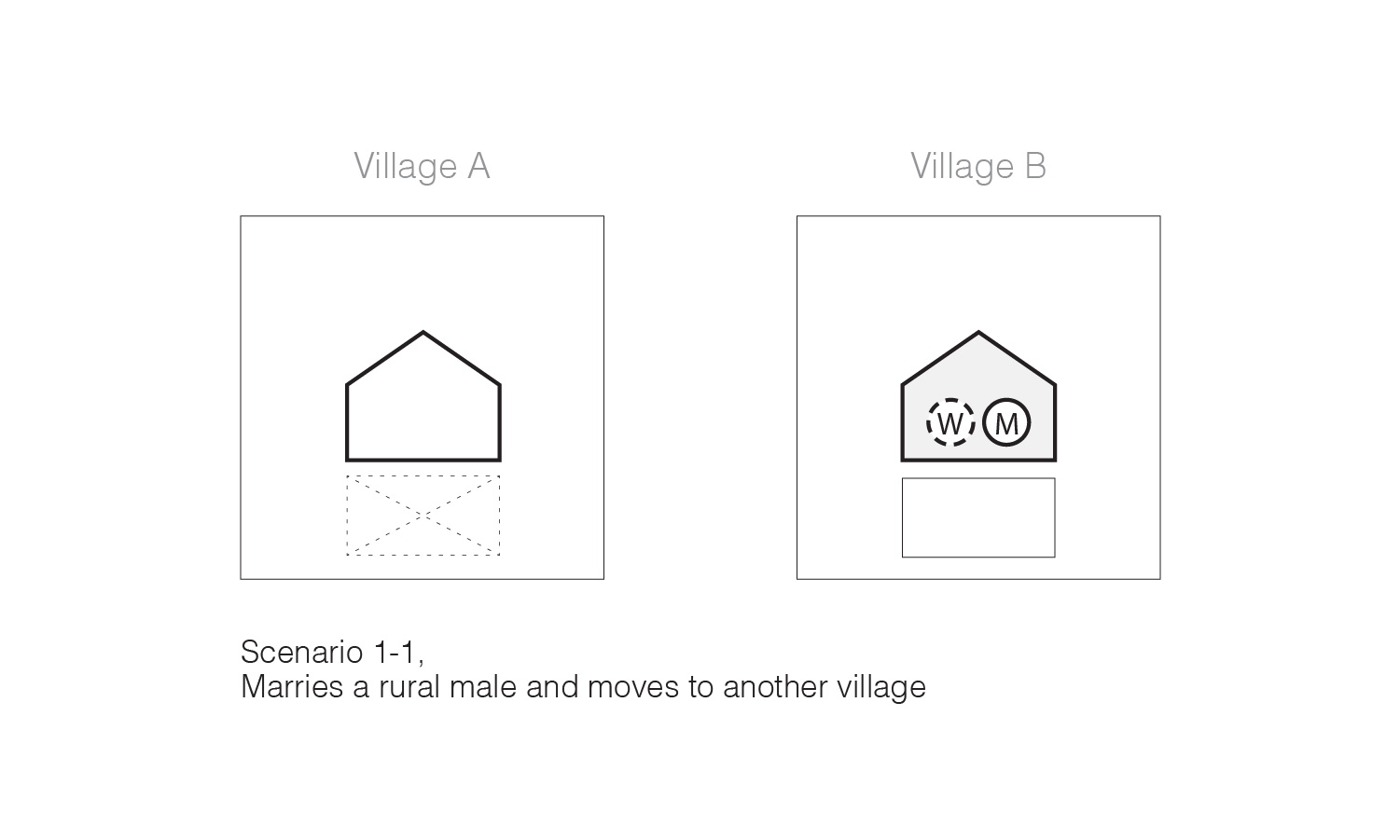

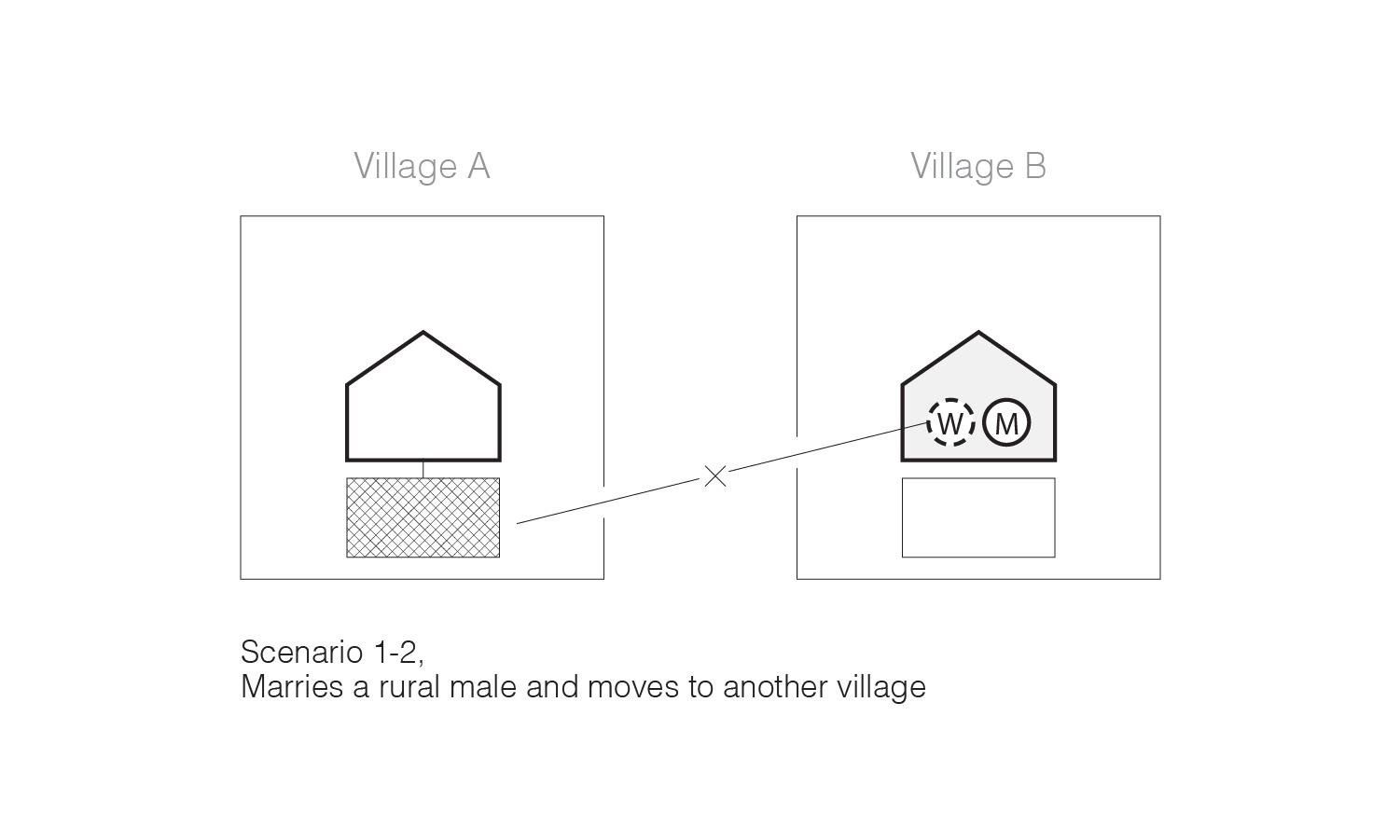

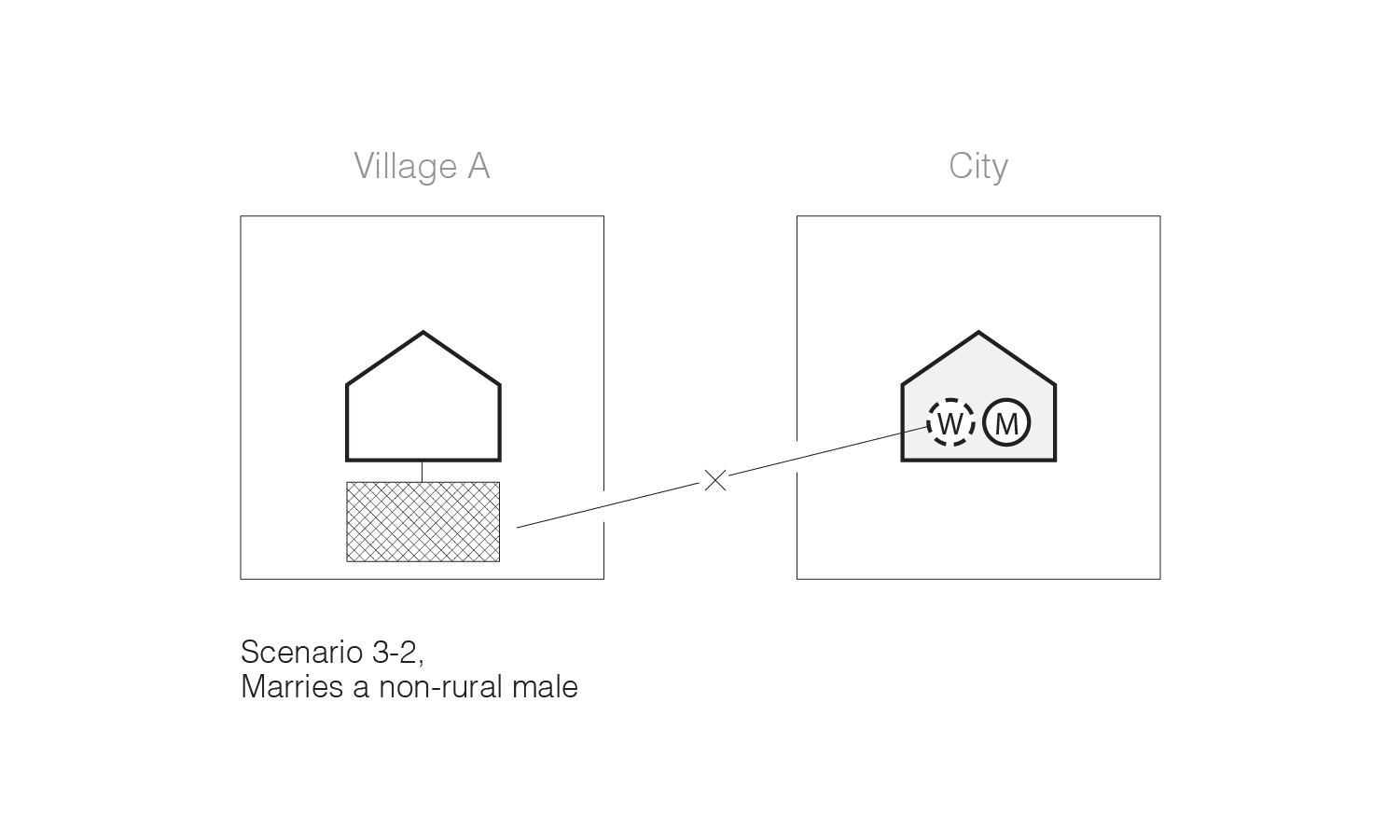

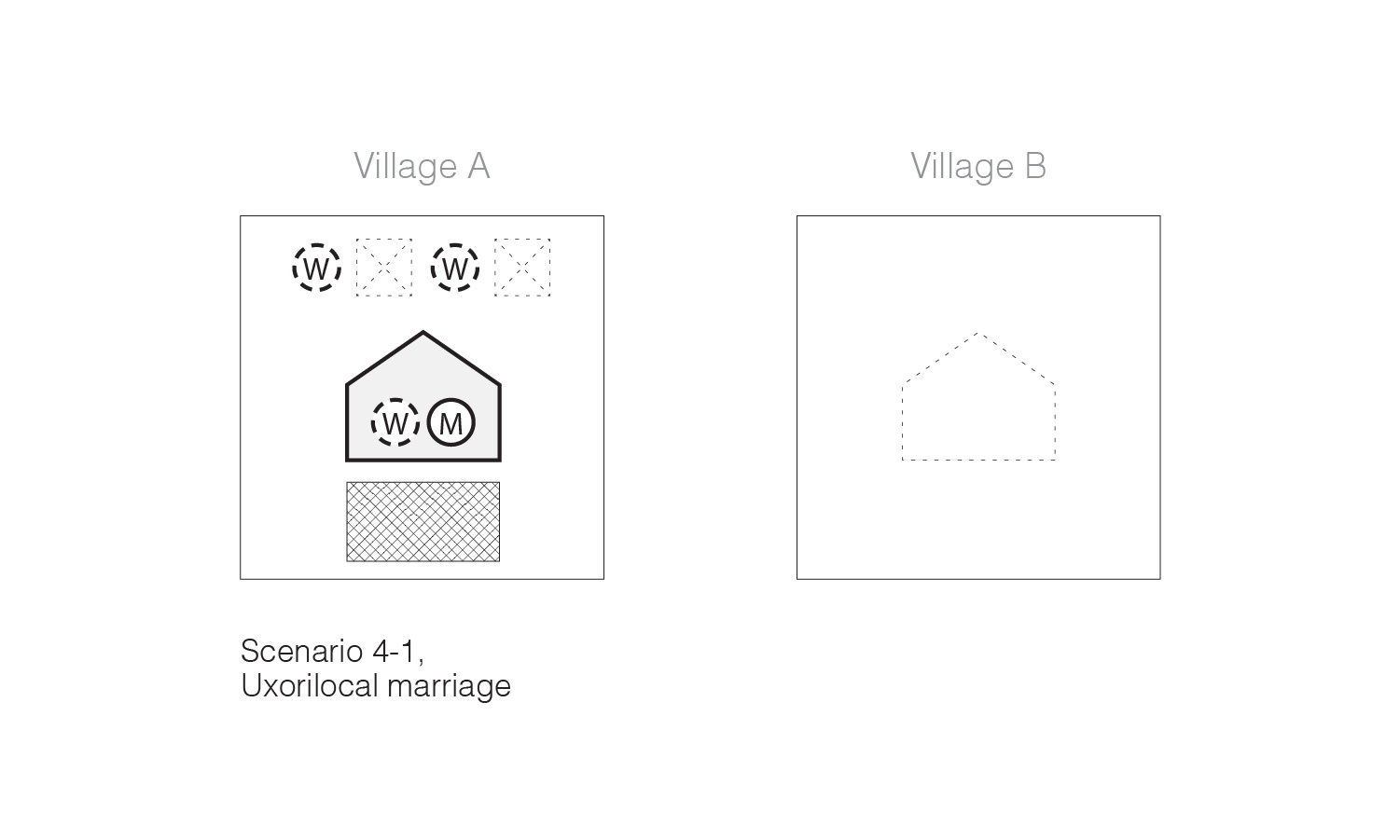

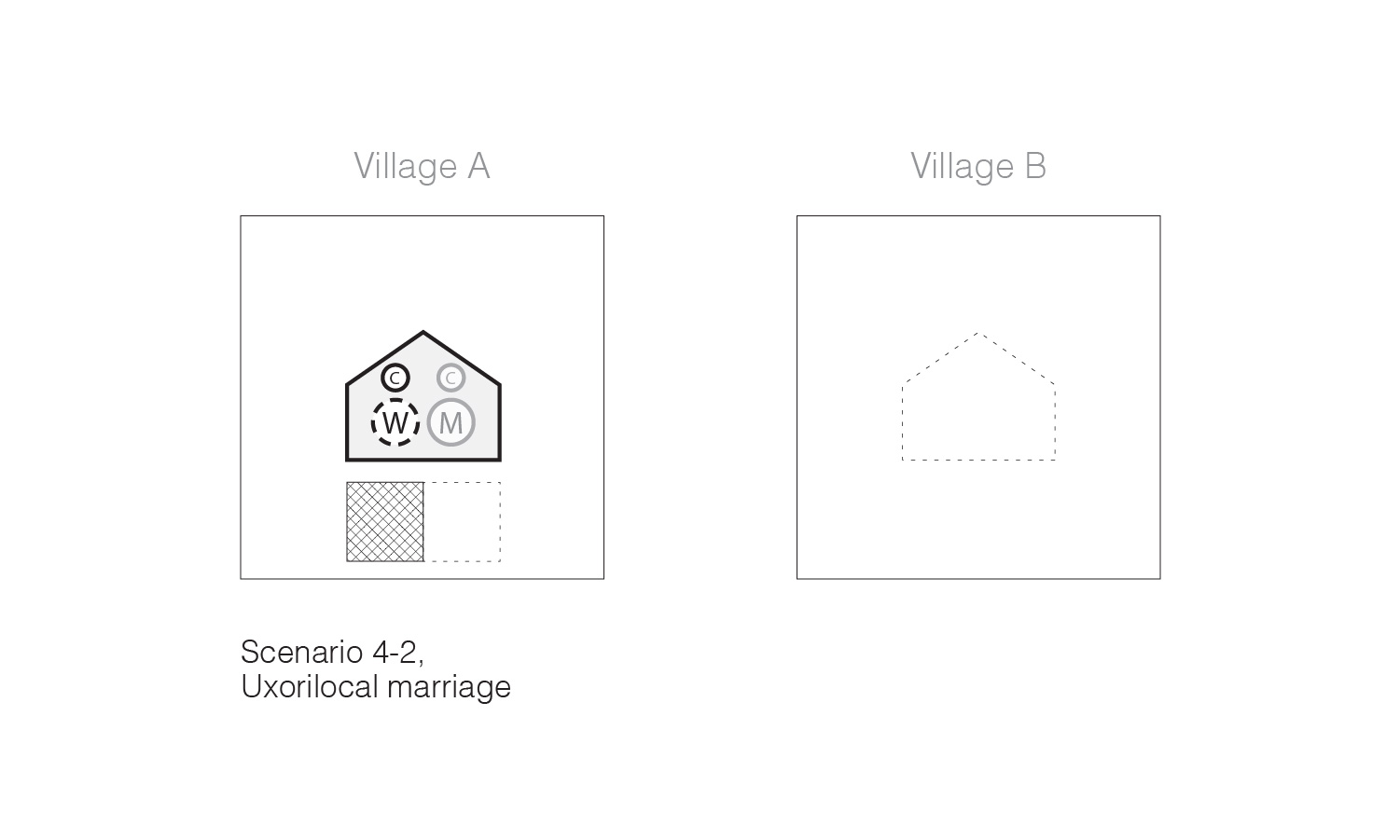

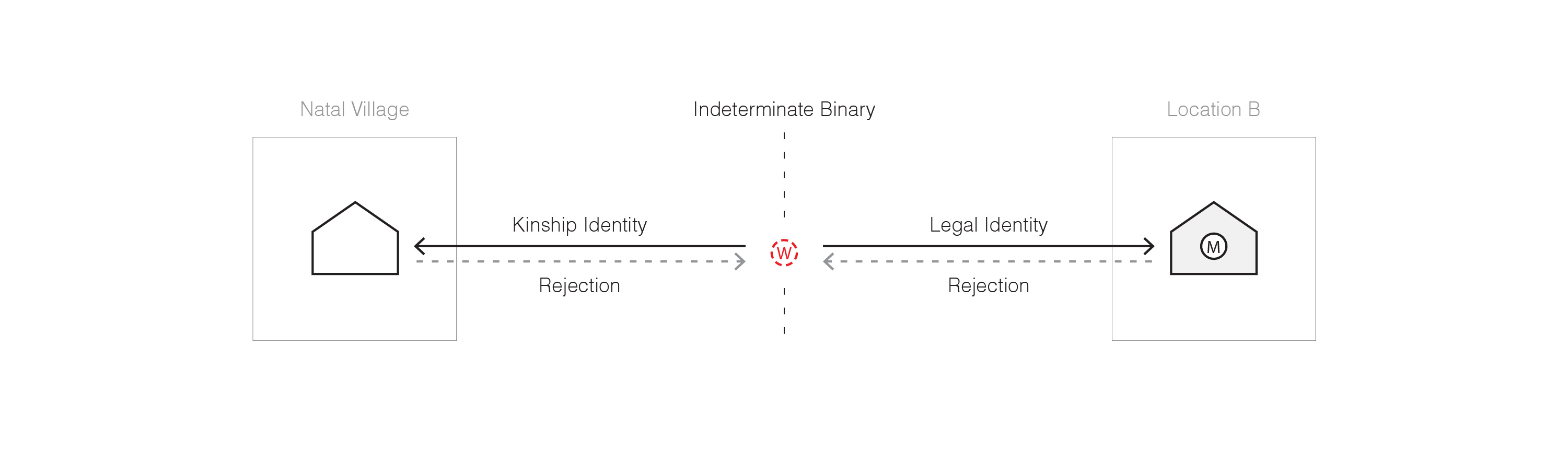

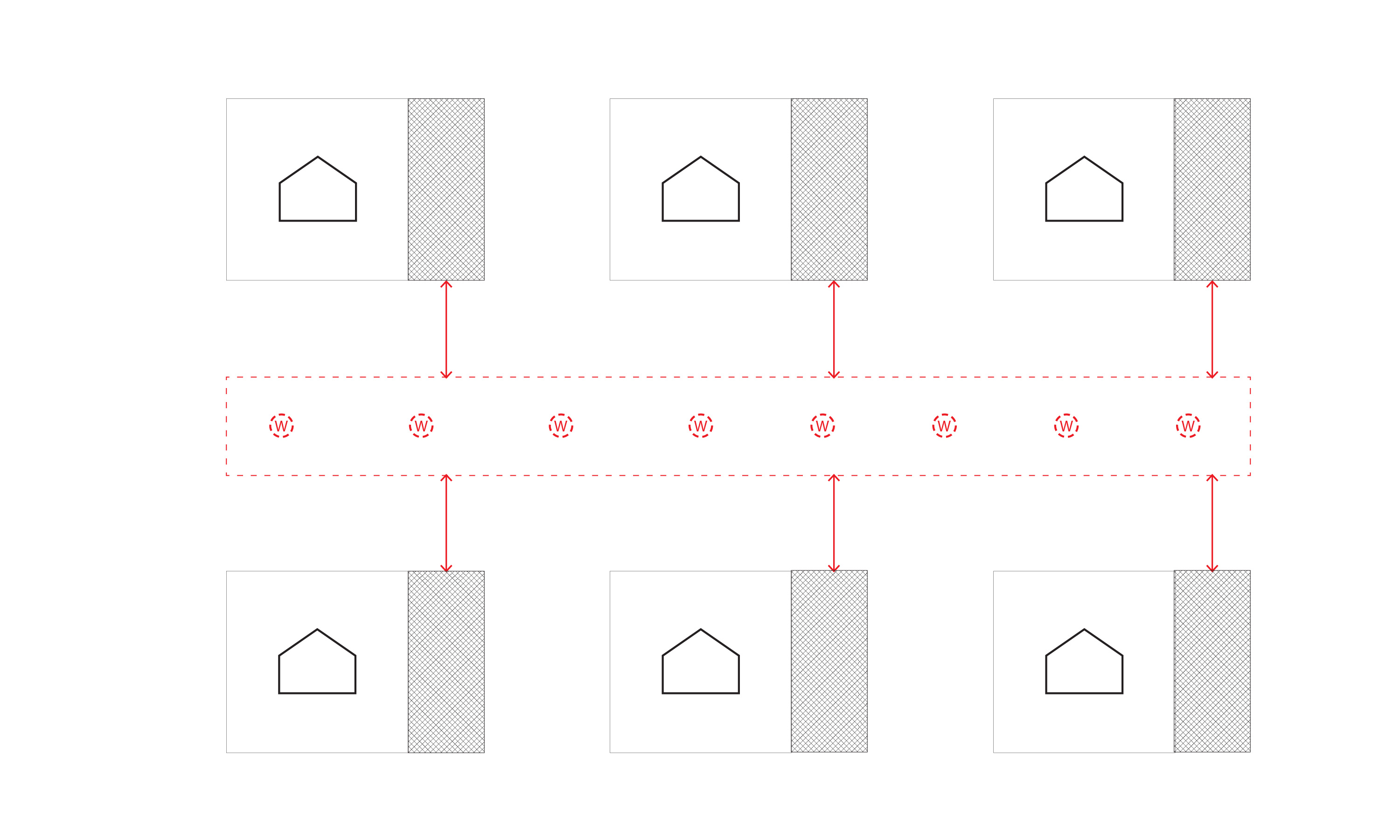

The series of diagrams suggest an internal conflict among three actors: the binary condition of the female’s identity, the sentimental ties that she has with both sides of the binary, along with the rejecting disposition of both parties. It is worth mentioning that the land itself does not show resistance against these actions;

land is not a factor in

jeopardizing women’s land rights. The rural land is malleable and fluid, it permits alterations and works with different hands; it is the ideological borders assigned to it that makes it seem static.

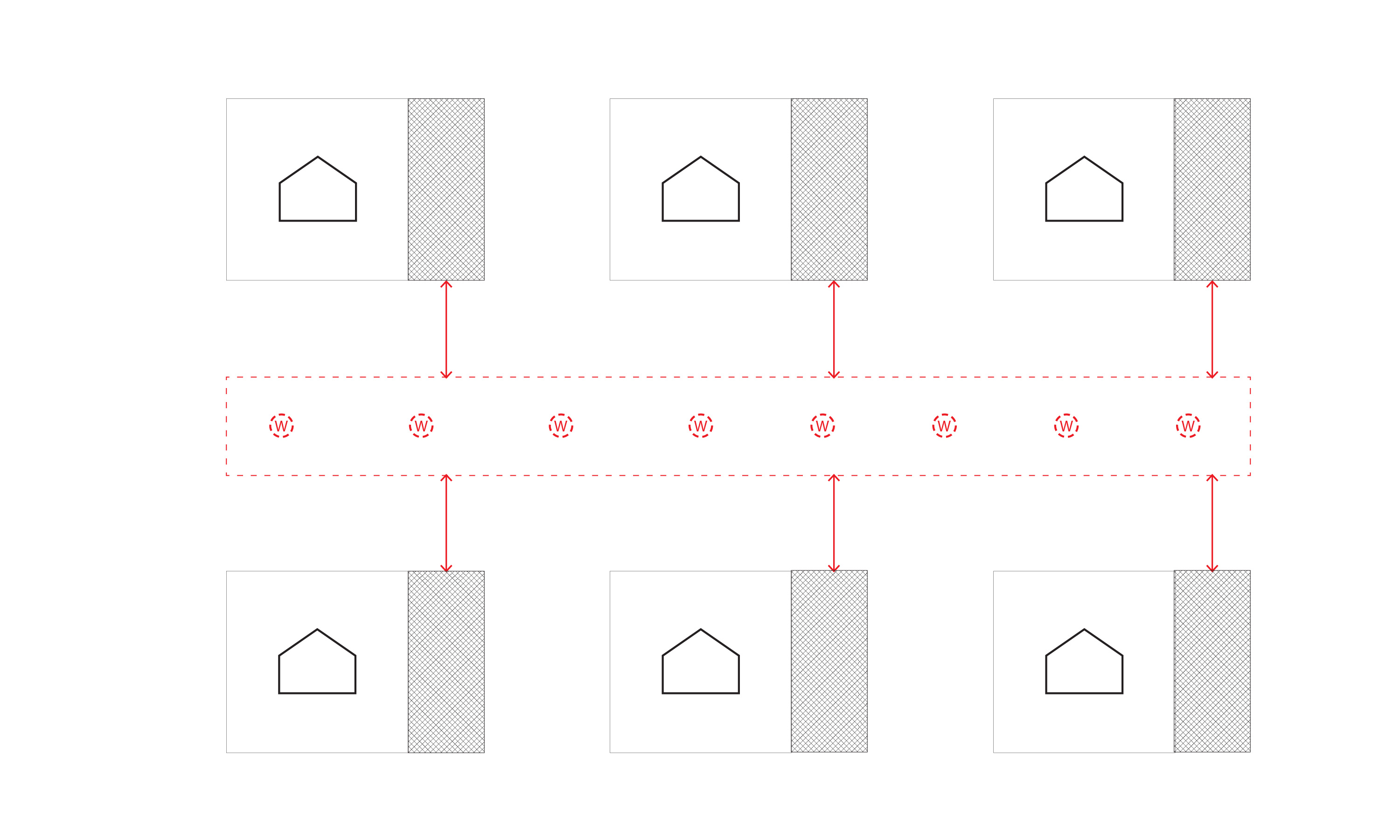

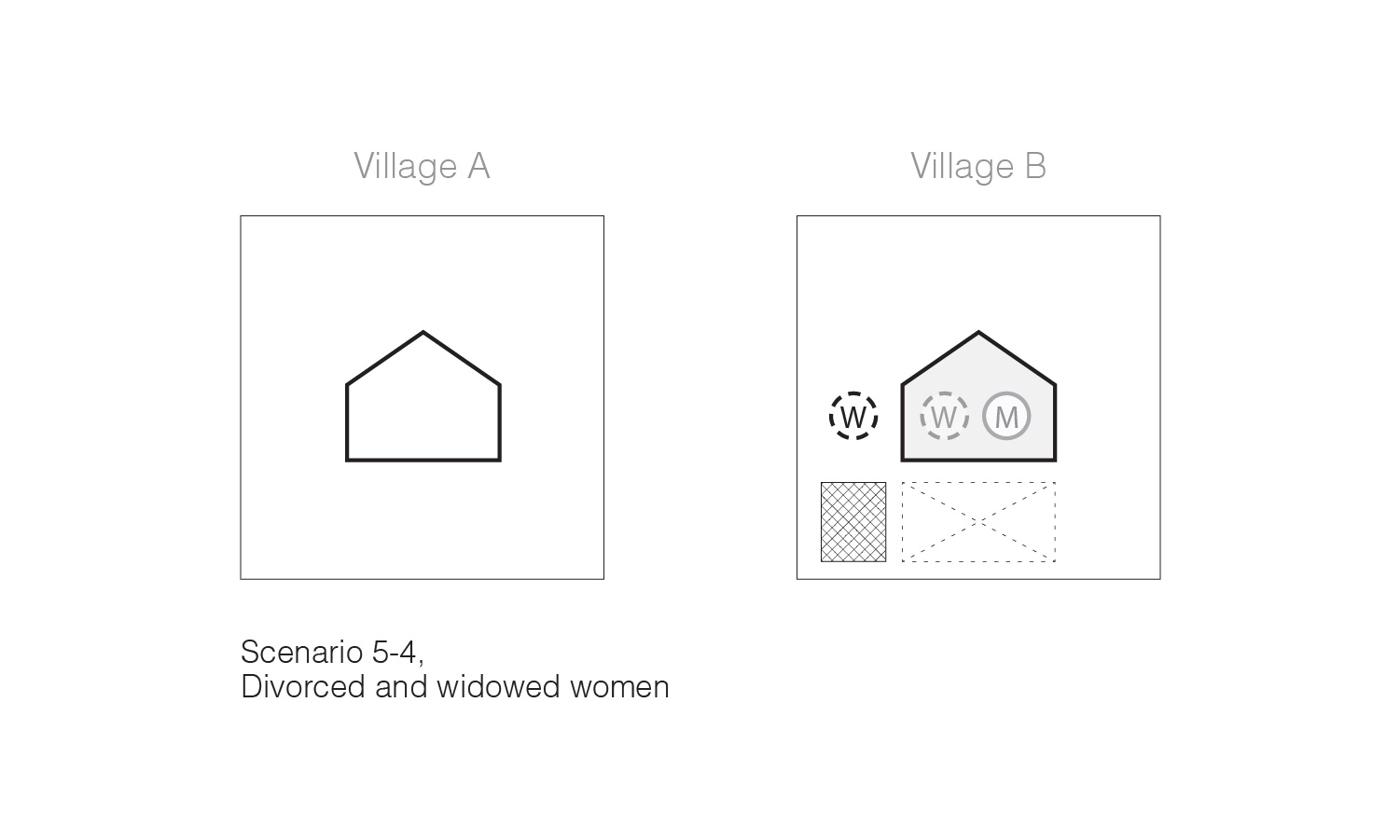

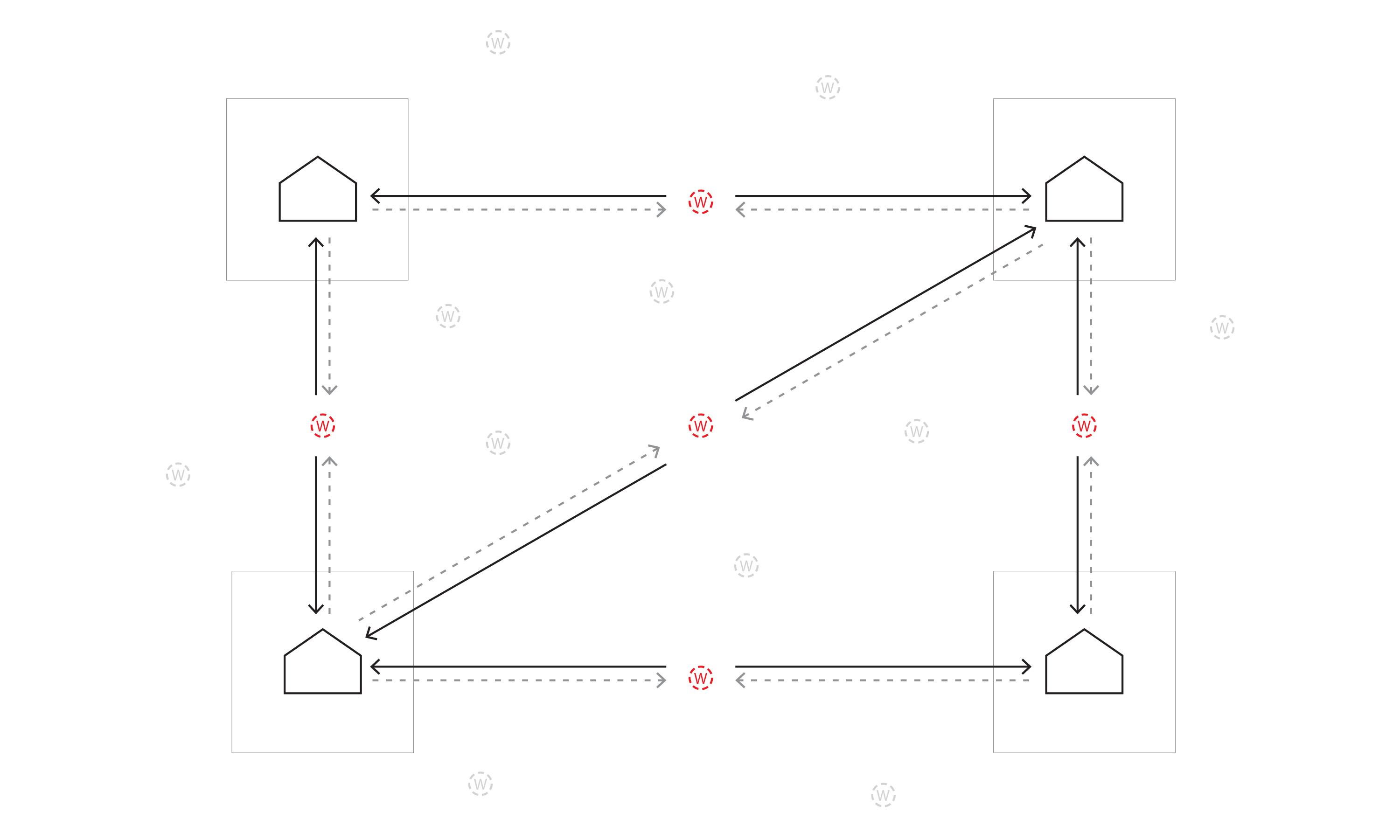

To also consider the potential impact of the new land allocation structure on a trans-regional level, it is productive to envision this network when similar behaviors start repeating itself. When the simple negotiation between natal village and new location is repeated, rural women’s displaced, “middle-ground” condition becomes the more stable default.

In other words, because women are the most mobile group in rural settings and they are in constant exchanges from one location to another, the state of being land-less and identity-less is the true norm. The image above shows the possibility of a large number of land-less women who remain invisible to their surroundings and disconnected from each other, therefore the new land distribution structure should function in the form of women’s collective.

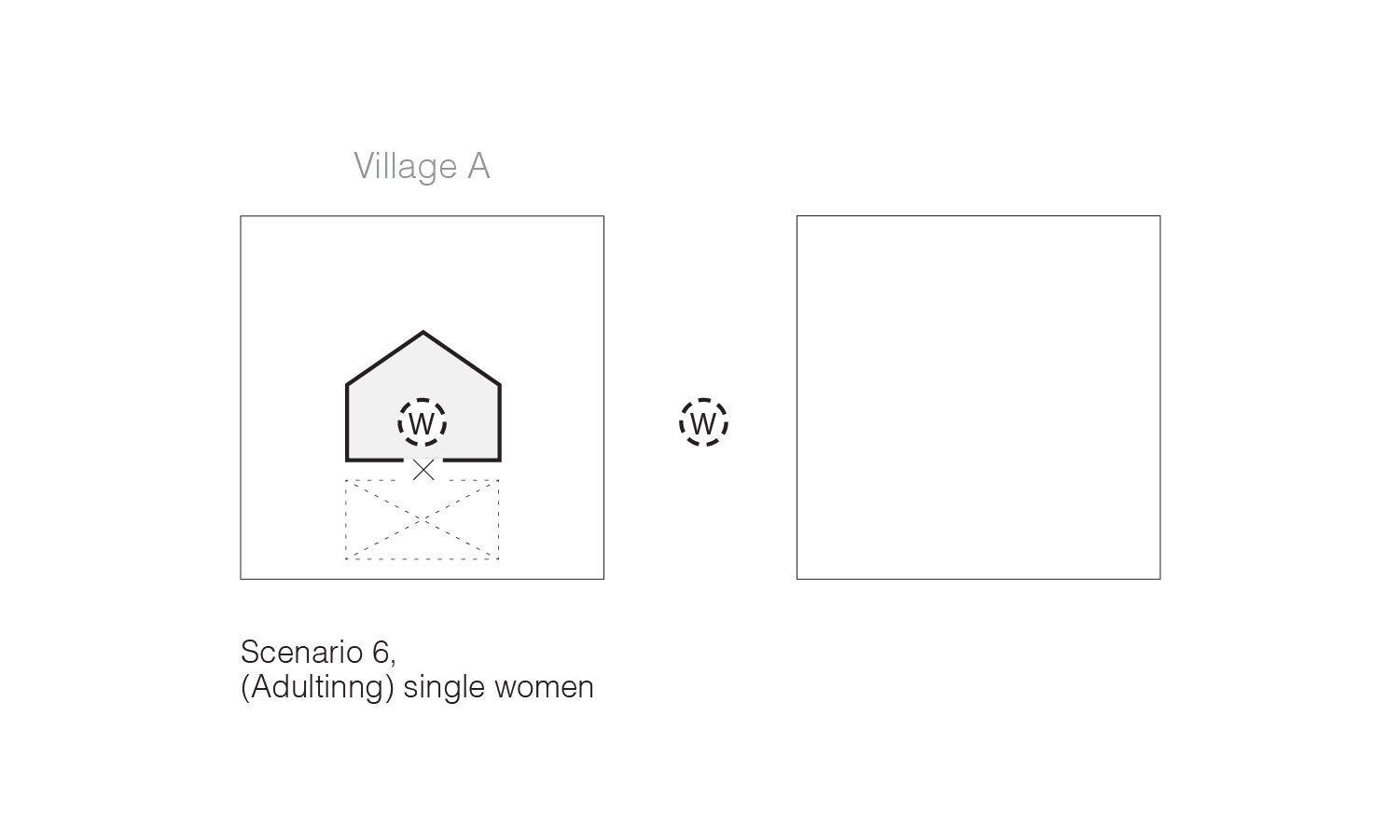

The last diagram shows how the restructured dynamics could free rural women from the current perplexing dilemma of being land-less and identity-less. Ideally, a trans-regional women’s community will claim an adequate portion of arable land in each village, and rural females can transfer their portions of land in a fashion similar to transferring credits among the collectives in different villages when her status changes. Functioning within a cross-village women’s collective allows rural females to be taken out of the constraint of binay identities, therefore making it possible to have a smooth transfer of land when her residence changes.

Having a physical establishment of land for a women’s collective can also have a reversal impact on the ideological structure of current land distribution, consequently modifying the disposition of the context. By bringing forward the number of women who are rightfully entitled to their land and pooling their production together, the visibility of their labour and production nullifies their systemic invisibility.

Having a physical establishment of land for a women’s collective can also have a reversal impact on the ideological structure of current land distribution, consequently modifying the disposition of the context. By bringing forward the number of women who are rightfully entitled to their land and pooling their production together, the visibility of their labour and production nullifies their systemic invisibility.

A women’s collective also connects women who are priorly disengaged with their community, thus giving more agency for advocacy in the current political structure of villager’s autonomy.

The gender-based structural violence against rural Chinese women shows an affordance to constructively reshape the dynamics between them and their hostile context. This essay proposes a trans-regional women’s collective that enhances their women’s physical and political situation in the current context, specifically by replacing the binary condition that makes their identity ambiguous with a third entity that they can always re-identify with. Aside from raising a collective voice for rural women in political settings, a cross-regional women’s community also encourages the fluidity of land itself, countering the ideological borders assigned by a biased infrastructure that has a disposition of isolating women from their land and related rights.

The gender-based structural violence against rural Chinese women shows an affordance to constructively reshape the dynamics between them and their hostile context. This essay proposes a trans-regional women’s collective that enhances their women’s physical and political situation in the current context, specifically by replacing the binary condition that makes their identity ambiguous with a third entity that they can always re-identify with. Aside from raising a collective voice for rural women in political settings, a cross-regional women’s community also encourages the fluidity of land itself, countering the ideological borders assigned by a biased infrastructure that has a disposition of isolating women from their land and related rights.