Formal Analysis I, Fall 2019

Instructor: Peter Eisenman

Instructor: Peter Eisenman

Bramante | Dissonance from Reconciliation

I’m interested in exploring the hierarchical presence, both rhetorical and structural, given to the different orders in the two projects. Because of their difference in rhetorical and structural priorities of the space, when encountering dissonant at their corners, the Cortile at Santa Maria used a subtractive language while Palazzo Ducale applied an addictive one, and they both left architectural hints of these methods.

The organization of the cortile at Santa Maria is defined by the voids and rhetorically subjects’ experiences, and as a result, the interior-facing side of the columns on the first floor had to give ways to the colonnade-facing side to make sure that the viewers’ experience is consistent, and the dissonance on the interior-facing side of the columns’ pedestals have to be sacrificed in order to make that structural system work.

On the other hand, the cortile at Palazzo Ducale prioritized the wall system, meaning that the disjuncture at the corner is a compromise in order to make sure that the mathematical relationships between the columns remain constant, and the gaps generated from the problem is filled up with the underlying structure: the wall. The hint of a circular column at the corner which does not work with the overall ratio is a compromise made to mediate between the grammar of the columns and the wall. The cortile at Palazzo Ducale is essentially a space enclosed by four walls yet at Santa Maria it’s dominated by a grid of columns.

Palladio | Mathematics introducing Structural Dominance

There are two major differences when comparing II Redentore to San Giorgio Maggiore. Firstly, the dominance of the crossing in each of the buildings are established in ways that disrupt the organization of the rest of the structures in diverse manners. Moreover, the mathematical tie of II Redentore with its surroundings are significantly more major than the other.

To be specific, In Redentore, the crossing is inserted into the classical transept church typology, and that insertion manner generated a sense of compression in both plan and elevation. The width difference of the crossing and the rest of the structure hints a sense of conflict, and the poche which places a buffer hallway between the articulated inside and the rigid outside supports the same argument. On the other hand, the crossing at San Giorgio Maggiore indicates a clear sense of expansion. The poche that confines the crossing contrasts with the one at Redentore, showing the crossing breaks free from the aisle and the transept surrounding it. The elevation carries the same characteristics as the crossing part ascends to lower than the transept.

Moreover, the two buildings also indicate two kinds of progression: the Redentore has a liner, progressive transition whereas at San Giorgio Maggiore, the organization is centrifugal, with the centre of the crossing being the optical also and organizational focus of the entire building, tying all other parts together.

Nolli and Piranesi | Figure-Ground vs. Figure-Figure

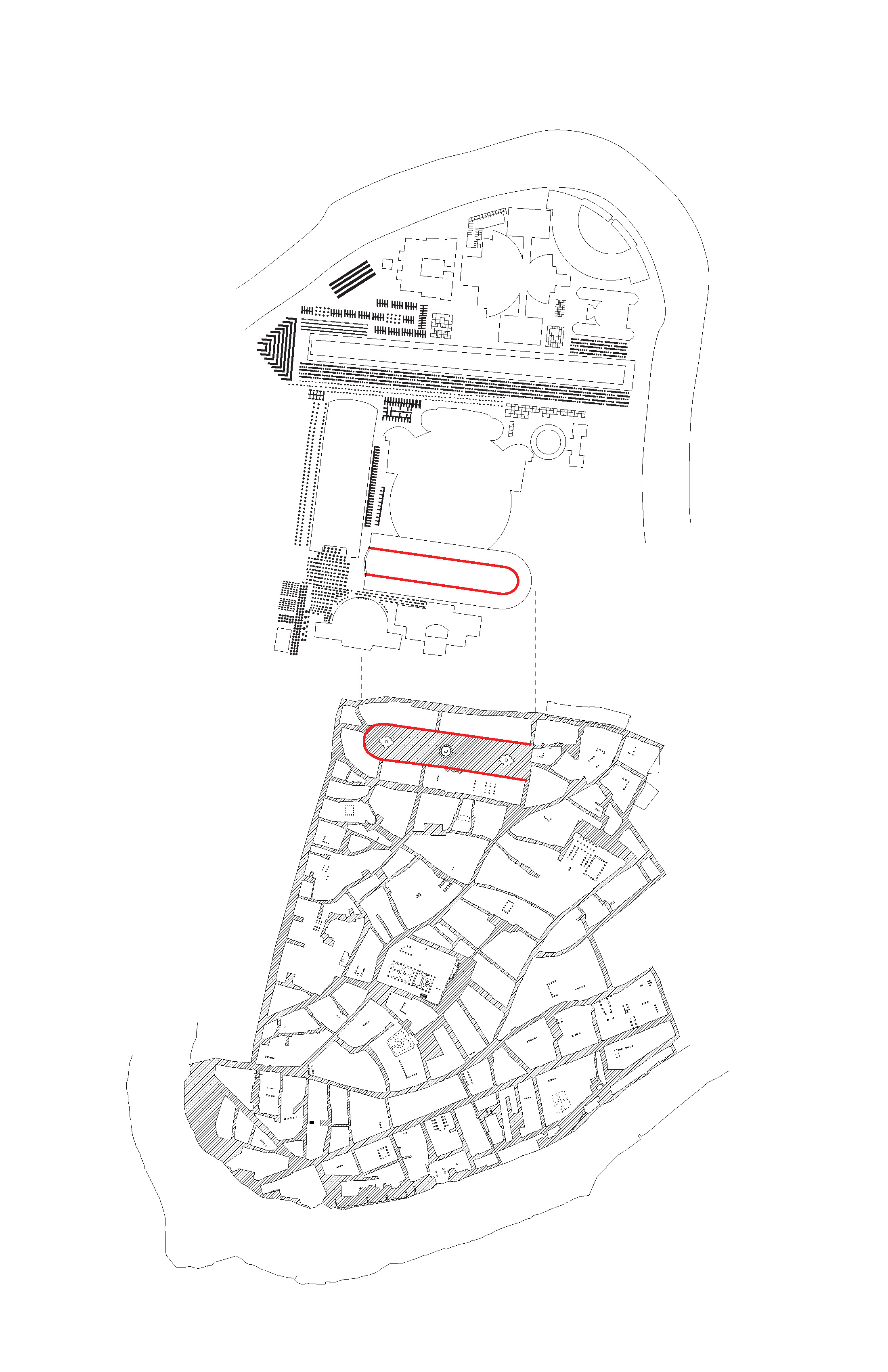

In ways that Nolli’s Map of Rome and Piranesi’s Campo Marzio differ, we can sense two drastically attitudes and approaches towards urban environments: figure-ground conditions versus archeological studies. Nolli brought socio-political factors into an archeologically scientific mapping of Rome, making it as “true” as possible. He understood the city as it is, and in his Map of Rome, architecture stands as parts of the city, the orientation and fabrics of the architecture is bonded with the streets and courtyards. In some ways, Nolli treated the architecture and the ground of the city as two-dimensional elements that are juxtaposed on to each other; the ground condition is like a blank canvas that needs to be defined by the architecture to become “city”.

Alternatively, Piranesi treats the city as a collection of obstructive elements pressed into the ground and pressed against each other. He also believed that immense elements, such as walls and columns, are what constitutes “magnificenza”, and that’s the reason why he populated the imagined restoration of Rome with numerous walls and columns that are individual, intrusive parts that don’t belong to any contained structure.

My drawing contrasts the different ways that Nolli and Piranesi treated the “leftover” space between the ground and the structures. Nolli respected these spaces because as part of the city fabrics, what is left over is as important as the what is built on the ground – they are two complimentary components that complete the city fabric. On the contrary, the streets disappear and are replaced with imaginary elements in Piranesi’s map, the city became a forest of immense structures that generates an arbitrary sense of scale, making the city a polulation of figure-figure conditions.

Even though the twin churches of Sta. Maria in Montesanto by Bernini and Sta. Maria dei Miracoli by Rainaldi are intended to create visual similarities, these two churches are vitally different structurally. When viewed in plan, the church of Sta. Maria del Miracoli is more compressed compared Sta. Maria in Montesanto, mainly because it appears to be a more “perfect” circle whereas the dome of Montesanto casts a dominating oval shape over the structure. It is understood that the difference in plan is for the two churches to create an optical delusion that makes the passengers see these two as two of the same origin from the entrance of Piazza del Popolo, yet the compression and expansion of the interior leads to a series of interesting organization of the individual elements.

There is one constant and one variable between the two churches. The constant is the actual dimension of the alter in bother churches, and to maintain this constant, associating parts of the interior has be to compromise and adjusted. The variable is referring to the way that the bays and the columns are calculated. From the aisle part extending into the alter, two bays in Montesanto translate into one bay in Miracoli. This conversion led to the emission of one side bay and a series of openings.

Furthermore, the grouping and overlapping of the interior reflects the contrasting sense of compression and expansion within the churches. Both church can be vaguely grouped into three parts – the entrance, the nave and the alter. In Montesanto, these three parts remain sequentially independent of each other, but in Miracoli, they intersept and negotiate with each other, consequently generating some unique poche.